Host Relationship/Adaptations

Host Relationship

They enter the host via ingestion of the eggs which mature through the digestive system and then work their way back to the large intestine where they spend the rest of their life. They aren’t too troublesome in small numbers but in large numbers they can cause more serious problems. They are more common in large numbers in older dogs.

Precautions

To prevent reinfection it is important to keep your yard free of feces to prevent ingestion of eggs. If it gets bad you may want to keep your dog from contaminated soils as the eggs can survive a long time.

Remember to keep your yard clean to prevent parasite infections

photo taken by me

Pathology and Diagnosis

In large numbers they can cause severe inflammation of the caecum leading to diarrhea, anemia, and poor health. The feces during this period contain a lot of mucus and can be flecked with blood. Veterinarians determine a whipworm infection by finding whipworm eggs in the stools. Fecal flotation is the most common way to find eggs in the stool but they do not float well in typical flotation mediums so they must be allowed to float for at least fifteen minutes before viewing.

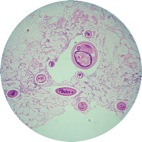

Trichuris vulpis egg under microscope- photo taken by Dr. Linda Sullivan from the University of Wisconsin- Madison School of Veterinary Medicine

Treatment

Whipworm infections can be treated with vermicides such as mebendazole or fembendazole but as they don’t work as well on juvenile forms and whipworms take about three months to mature, the drugs should be given about once a month for the three months. If you don’t keep your dog from infected soils reinfection is very possible. Extreme emphasis is put on the need for sanitation.

Adaptations

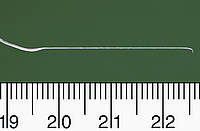

They have evolved specifically as a parasite of dogs. As a species they are characterized as whip-shaped with eggs shaped like lemons with distinct plug at each end. They can live for up to two years in the egg form as they are extremely resistant to environmental conditions. They will not hatch until they are ingested. The Trichocephalida are characterized by their stichosome esophagus which is a capillary tube surrounded by a column of stichocytes. T. vulpis embeds itself in the large intestine, with a spear-like projection on its mouth, where it carries out its parasitic lifestyle.

Nutrition

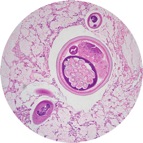

T. vulpis is a blood-feeding nematode that takes in all of it’s nutrients from the dog’s caecum. They consume less than hookworms but in large numbers they can cause significant anemia. As with all parasites they are harming the host by obtaining these nutrients. As adults they only grow to about 4-7 cm but when these guys line the intestine they can add up and do considerable damage with what they consume. That is noticeable when you notice blood in your dog’s stools. They have a complete digestive tract in which extra-cellular material moves through the pseudoceolomic cavity as shown below. They do not have a circulatory system, nutrients just move through the pseudoceolom to the tissues that need it and for the most part that is reproductive tissues that constantly need nutrients to keep up with the rapid reproduction.

Fig 1: Trichuris vulpis courtesy of Bayer Heath Care Animal Health and are prodected by their General Conditions of use

Trichuris vulpis cross section under microscope-photos taken by Dr. Linda Sullivan from the University of Wisconsin- Madison School of Veterinary Medicine